11 Aug Yom Kippur Guide

Yom Kippur: The Day of Atonement

Understanding the Most Sacred Day in the Jewish Calendar

- Copy Link

Yom Kippur: The Day of Atonement

Understanding the Most Sacred Day in the Jewish Calendar

- Copy Link

Yom Kippur is considered the holiest day of the Jewish year: a 25-hour stretch of quiet, focus, and spiritual renewal. For many Jews around the world, it’s a day to pause, look inward, ask for forgiveness, and step into the new year with clarity and purpose.

It’s not about punishment or guilt. Instead, it’s a powerful opportunity to start fresh, clean the spiritual slate, and reconnect with yourself, with others, and with something greater.

A Day Set Apart

Yom Kippur falls on the 10th of Tishrei, about a week after Rosh Hashanah (the Jewish New Year). It marks the final day of the Ten Days of Repentance: a period when people are encouraged to reflect, apologize, forgive, and make real changes.

“For on this day He shall effect atonement for you to cleanse you. Before the Lord, you shall be cleansed from all your sins.” — Leviticus 16:30

One of the names for Yom Kippur used in the scripture is the “Sabbath of Sabbaths,” and for good reason: it’s a day of complete rest, when even the usual Sabbath restrictions are taken a step further.

Yom Kippur is most known as a fast day, in which Jews abstain from eating or drinking. The fast, which lasts 25 hours, is one of the most widely observed Jewish rituals, even among secular Jews. Instead of work, food, or entertainment, the focus shifts completely to:

- Teshuvah (repentance)

- Tefillah (prayer)

- Tzedakah (acts of charity)

Name, Origins, and Traditions

“Yom Kippur” literally means “Day of Atonement” in Hebrew: “Yom” (day) and “Kippur” (atonement or covering). The Torah talks about this day in several places, including:

- Leviticus 16, which describes the High Priest’s temple service

- Numbers 29:7–11, which outlines sacrificial offerings and observances

- Leviticus 23:26–32, which commands it as a day of complete rest

Yom Kippur is also known by other names, including Shabbat Shabbaton (“Sabbath of Sabbaths”), Day of Awe (in the context of the Yamim Noraim, or “Days of Awe”), and the Holy Convocation (as described in biblical texts).

Historical Significance

The very first Yom Kippur was the day Moses descended from Mount Sinai with the second set of tablets, after the sin of the Golden Calf. This act symbolized God’s forgiveness and is seen as the foundation for the day’s atoning power.

In ancient times, Yom Kippur was centered on a singular and awe-inspiring ritual: The High Priest, dressed in pure white, would enter the holiest section of the Temple, the only day of the year this was permitted. There, he would make an offering and ask for atonement on behalf of the entire nation.

Laws and Customs

Observing Yom Kippur involves a range of spiritual and physical practices that shape the entire 25-hour experience.

Preparations (Erev Yom Kippur) & The Fast

- Kapparot: A symbolic act in which sins are “transferred” to a chicken or coins, later donated to charity.

- Se’udah Mafseket: A festive pre-fast meal eaten before sundown.

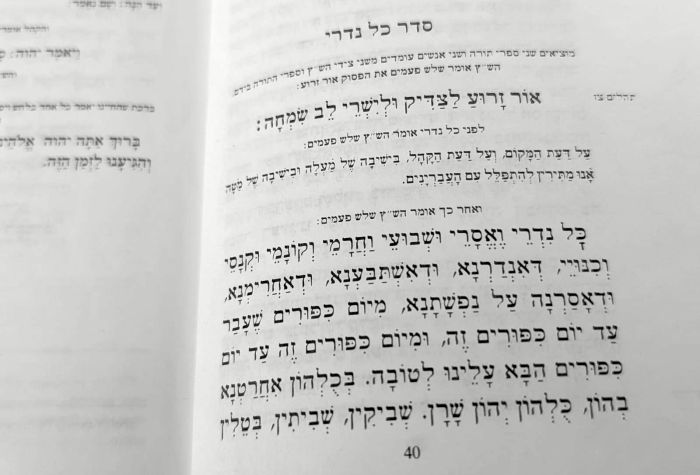

- Hatarat Nedarim: The annulment of personal vows, typically performed before the holiday.

From sunset to nightfall the next day, observers abstain from eating and drinking, doing work, washing or bathing, anointing themselves with oils or lotions, wearing cosmetics or leather footwear, and engaging in sexual relations.

Symbolism & Prayers

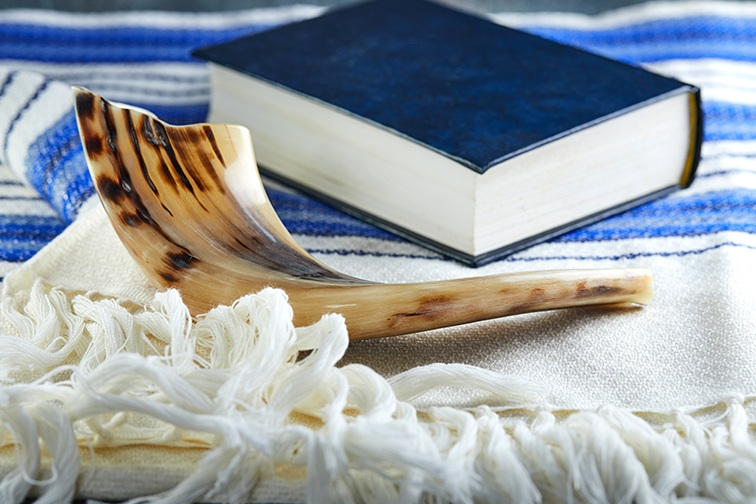

Many wear white garments on Yom Kippur to symbolize purity, humility, and the desire to emulate angels. White is also a nod to what the High Priest wore on this day. In ultra-orthodox communities, men often wear kittels (simple white robes), which in many synagogues are specifically worn by the cantor on Yom Kippur as well.

Yom Kippur includes five unique prayer services (instead of the usual three):

- Kol Nidrei and Ma’ariv (Evening): Known for its moving melody and for annulling vows.

- Shacharit (Morning): Includes Torah reading and confessional prayers.

- Mussaf (Additional): Prayers that substitute the extra sacrifices once offered in days of the Temple.

- Minchah (Afternoon): Features the reading of the Book of Jonah.

- Ne’ilah (Closing): A powerful final plea as the gates of heaven symbolically begin to close.

The final shofar blast at the end of Ne’ilah marks the conclusion of Yom Kippur, signaling a fresh start.

Yom Kippur in Israel Today

In the State of Israel, Yom Kippur is unlike any other day of the year, both religiously and culturally.

Across the country, all public transportation halts, airports close, and TV and radio go silent. Shops, restaurants, and offices shut down, and only emergency services operate as per usual.

For many Israelis, even those who are secular, this day holds deep significance. In fact, it is the most widely observed Jewish ritual in the country, with 60–70% of Israeli Jews fasting on Yom Kippur. And though many Israelis don’t attend synagogue regularly, Yom Kippur draws even some of the most secular into prayer spaces, community centers, or even outdoor minyanim (prayer groups).

Further, with the roads empty of cars, many kids and teens ride bikes, skateboards, and scooters through city streets and highways. While it’s in no way rooted in religious law, this has become an iconic part of Yom Kippur in Israel, blending tradition and modern secular culture.

A Time to Reflect and Renew

However it’s observed, Yom Kippur is a day of deep meaning and impact. It invites everyone, from religious to secular, and from young to old, to pause, reflect, seek forgiveness, and begin the year with purpose and clarity.

At The Jewish Agency, around the Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur period, the organization has often organized some sort of meaningful initiative to bring Jews together and to foster their connection to Israel. During the pandemic, we invited Jews around the world to submit notes online to then be taken to the Kotel (Western Wall) at a time when flights were scarce, making upholding the tradition in-person difficult for many who would otherwise do so themselves at the holidays. And The Jewish Agency’s religious streams educational programs teach participants all about the Jewish holidays, including the above information and much more, as part of our efforts to create lasting bonds between Jews and Israel.